In February of the last year of my undergraduate program, my girlfriend took me up to her family’s condo. We spent the week there doing minimal schoolwork and enjoying a quiet time away from our hectic student lives in Vancouver. The glass buildings were replaced in the view by mountains, some of which Bronwyn could name. Sadly. I never managed to

commit any of them to memory myself and got to know parts of Whistler in a way, but without ever really finding a proper sense of direction. At this point in time I was still fairly certain that she was not in favour of romantic gestures that relied on any kind of overwhelming surprise, though I should’ve known from her love of music festivals and dancing that I needed more to excite her than relying on quiet techniques like reading and writing. My dependence on those quiet things, I think, is perhaps the reason why there have been so many books exchanged between us. For Christmas she gave me a copy of A Wild Swan by Michael Cunningham, with illustrations by Yuko Shimizu. The book was in my backpack while we were in Whistler but I never pulled it out in fear that she would see the coffee stains on some of the pages. The frustrating thing was that I had not begun to read it before I had stained it. Eventually I told her I had it and she started to read it aloud to me. After she flipped through the pages a few times and deciding that it was best to read it in chronological order, she read Dis. Enchant, which serves as an introduction, and A Wild Swan: the first story. The writing was more profane than I had expected and full of black humour that is exactly what I should

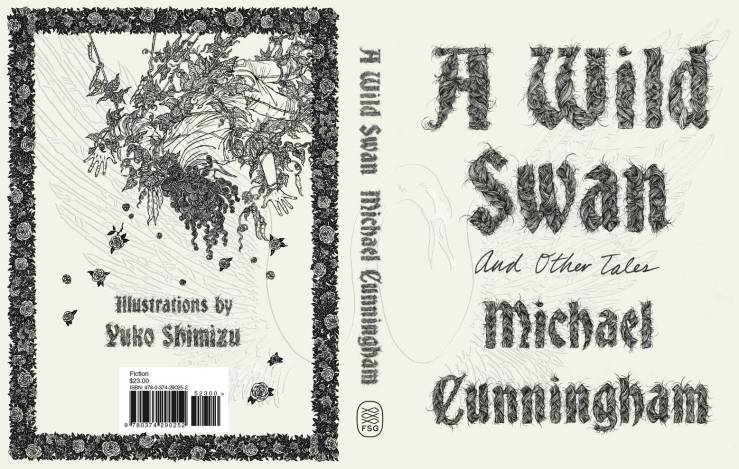

have. I had assumed from the gentle and precise cover design by Shimizu that the book would be full of delicate and beautiful stories with happy endings,, maybe mixed with one or two of those stories intended to make you cry. The design had given off the impression to me of a fireside book; the sort of thing one reads while avoiding the cold.(Really, any book can be made that if it is read next to the fireplace, but just as some books are meant to be enjoyed in a state of mind far from sober, some beg to be read while avoiding frigid weather).

A Wild Swan concerns a royal family, as the fairy tales it mocks often do, wherein the stepmother queen of thirteen princes and one princess, turns the boys into swans. The princess learns that in order to do the magic that returns her brothers to a human form she must make them each a coat of nettles collected from a graveyard. Before she is caught she manages to make eleven full coats and one that is missing an arm. The swan-brother who receives this coat is turned back into human form, save for one arm that remains a swan wing. The story ends following the swan-armed prince into a desolate city life where he rehearses pickup lines he never uses in his head, lives in a dreary apartment and regularly goes to a bar surrounded by others afflicted by partially or entirely uncured curses. It takes an anachronistic turn in what is chronologically the resolution but feels more like falling action. It mentions televisions and other technologies that seem out of place in a story about a kingdom where they are still afraid of witches. No, the fireplace is not what this story was written for, but it is closely related to them, especially with Bronwyn’s voice. It’s also a change to the fireside that I would appreciate because a “calm” fireside seems a little outdated to me. That fireside seems part of bourgeois history of the early 20th century; the place of books like Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, which flaunts the Christmas epiphany as an end to the bad nature of man. Dickens is possibly the patron saint of Christmas stories, just as Thomas Nast is the near-secret patron saint of Santa Claus, Coca-Cola and fighting the mob with editorial cartoons. Both of them now lost as subjects and made entirely into capital objects in the world I live in; a world where the fireside story is cinematic nostalgia. That is, that it seems to emulate images of a comfortable position familiar to me from the screen that is easier to imagine in the third-person, which is a longing for something I will never really be able to experience because reading comfortably really means having a setting to forget so as not to be distracted.

Bronwyn finished A Wild Swan and marked off the page where the next story began and I told her that I wouldn’t pick it up and read it myself without her. She is unaware, I think, that when I think poetry, my mind jumps instantly to her. Before her there were poets I could associate with the people who had suggested I read them, and for a while it was only T. S. Eliot that had me thinking of her, but I think it was because I read a poem that Bronwyn had written before we knew each other well, that when I think of poetry I think of her. That isn’t to say that her body translates before me into poetic metaphors, it is to say that they are synonymous and not whole as concepts without each other. I am all too aware that one of them is older than both of us, as old as democracy and philosophy, but I have not known it that long and know Bronwyn better than I will ever know poetry, so fundamentally it is hers as I see it.

At the time, in Whistler, I was listening to the novelist Lawrence Hill talk on blood in his set of lectures for the CBC Massey Lecture Series. Though I was thinking much more about the series Adam Gopnik had broadcast in 2011. Gopnik, an essayist, had talked about winter in his lecture series. Specifically, he talked about the modern winter and he argued that it was born out of the ability to observe winter painlessly. Suddenly, winter, after the invention of windows that kept out the cold, and heating that kept the home warm, a painter could appreciate the sublime white and not merely survive it. Gopnik began lecturing about a Romantic Winter, in which the season was to be enjoyed for the first time in history. The winter described by the poet William Cowper as “the king of intimate delights.” He goes on in his four lectures to describe winter as Radical, Recuperative and Recreational, ending with an almost somber lecture titled Remembering Winter. The most important of that series to me as I was listening to them was Radical Winter which begins with a reminder that the true setting of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is the Canadian Arctic and that almost the entirety of the rest of the story is a flashback, or at least framed by Dr. Frankenstein as he recounts the events that led him to the north. Most of the lecture describes expeditions to the North and South Poles, emphasizing their futility and the delusion that there is something to find. It’s a foolishness chasing fantasy that is the stuff of legends. A ship goes out year after year to find the ship that had preceded it, knowing almost full well that they were to be lost as well. “Paradise is an island, but so is hell,” writes, Judith Schalansky (“Beautiful,” responded L). Really though, they are both places of colonial dreaming that rarely amount to anything more than the unnecessary death of travellers or those living in the places they have travelled to. A North Pole at the time was only worth travelling to as a storytelling experience and not yet a proper geographical study. To be fair, the crews that believed themselves to be brave didn’t know the pointless nature of their heroics and I wonder if it relates to a word Gopnik introduces in Remembering Winter: vernalization. It’s a botanical term that describes the process of seeds that can only thrive in spring if they have gone through the severity of winter. The Israelites can only live in Paradise if they spend forty years wandering the desert; Scrooge can only be generous once he has been frightened into that mindset; silence can only be welcomed after overwhelming noise, just as noise can only be welcome after overwhelming silence. Without a season of overwhelming noise or silence, they are merely noise and silence; they leave love irrelevant and life monotonous.

It was Thursday when we headed back to our lives in Vancouver. In Whistler we had spent time in the Village, gone to see a film (Pride and Prejudice and Zombies), cooked for each other (she was much better at it than I), and she thought about going skiing but never did. We looked at the stars on a walk and she named a few constellations, not knowing many but still more than me. Not much of what we did there together was new but it happened somewhere different for us and we spent more hours together in a row than we had previously. If we are offered any sort of poetic preludes to the sort of things that hurt us, the connection this had to the event that had me in tears two weeks later is unclear and all I know is that on the drive home I thought Bronwyn might be sick of the noise I can produce but was relieved when she stayed a few more hours at my home and we silently held each other in my bed during that time. We had agreed on the ride home to return to the roads leading to Whistler which are full of landscapes we thought could be worth drawing. Landscapes are something that have never held my attention, I find them tedious to examine and uninteresting. Maybe it’s because I lack the knowledge to speak about them. Maybe it’s because when I was younger than twelve I took a ride on a train with my grandma who told me that when she was young, she never understood why adults would tell her to look out the window at the landscape because it was so boring. As I grew older, she said, I began to see things I had not appreciated and learned to see a new kind of beauty in it. My grandma had also told me around the same time that because I could draw I could probably have a very successful career as a dentist. I don’t think she was aware that the job has the highest suicide rates of any profession when she gave me that advice. Maybe for that reason I could classify dentistry and landscapes in the same category: things I have been told to like but choose not to out of insolence. I will admit to enjoying drawing the landscape even if I rarely go back to

look at them. It provides a challenge to my techniques that have almost all been honed to representing figures. Painting the landscape has always been something that I reduce to a simple green and blue, or blue and white if it is winter. Blue and blue is a seascape, and I can’t help but wonder if the Atlantic Ocean looks different when looked at from the different parts of its coast, or if it all just blends into the same image when it is separated from the land. Maybe it is all in the eye of the beholder: mountains are only really the mountains of Whistler and British Colombia and I designate them amateur terms like the smaller ones and the bigger ones; the ones where I love and the ones where I have been loved; the small number I’ve been to, the ones I might one day go to, and the majority that I will never be on, and will rarely think of.

You must be logged in to post a comment.